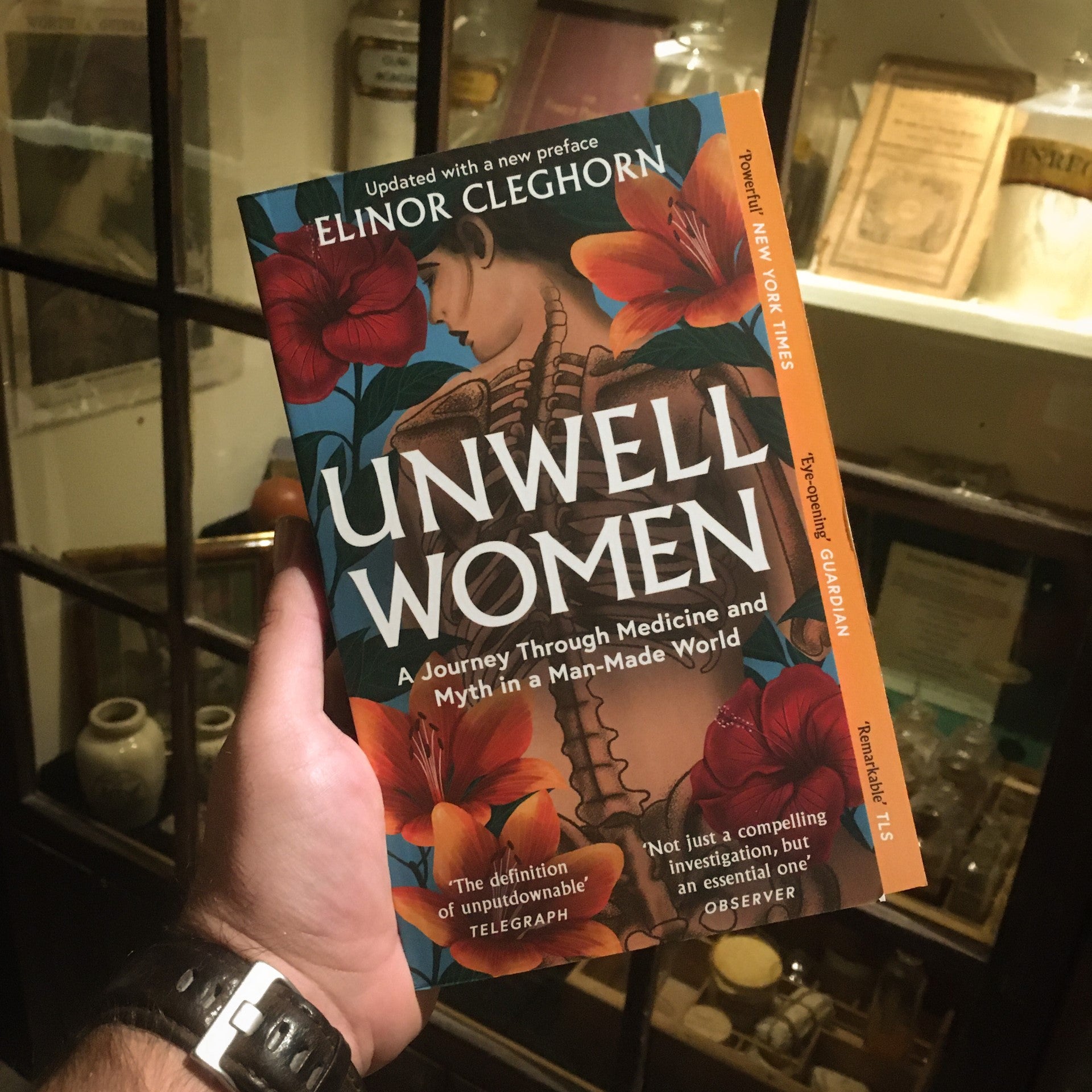

Each month we review a book from Mildred's extensive library. This month's book is Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn, reviewed by Jenni, the museum's Community Engagement Officer.

Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn is a brilliant, frustrating, and fascinating look at how male-dominated healthcare has shaped understandings of female health. Travelling from ancient Greek understandings of wandering wombs that could only be controlled by childbearing to modern conceptions of chronic illness as fabricated, Cleghorn shapes a story about a side to medical history that is rarely considered, despite affecting half the population.

Throughout, Cleghorn’s own experiences of being an unwell woman shine through – her life and health rely on those who have come before. Her own lupus, which previously would have been fatal, is diagnosed based on knowledge that comes from past people affected by the condition. However, she still found herself failed by a medical establishment that often minimises women’s health needs, her own chronic symptoms undiagnosed for many years, nearly costing her life and that of her son. This personal knowledge, of what it is to be ill and unheard, shapes her examination of the past, and draws connections between ancient history and what happens in medicine today (focussing mostly on the US and UK).

The book is split into three sections – Ancient Greece to the Nineteenth Century; Late Nineteenth Century to the 1940s; and 1945 to The Modern Day. Cleghorn traces how ideas of hysteria evolved over time, and how medicine has altered to control and limit women’s bodies, their sexuality and their minds. She also draws a distinction between symptoms that can be seen and measured and those that are experienced by the patient herself, showing how those lived experiences of what it is to be a woman with a body have been minimised and ignored by a medical establishment that historically thought women’s minds too fragile to be educated.

Cleghorn addresses contemporary issues and the theories that restrict women’s lives, highlighting how they trace back to historical and incorrect beliefs and cast a real shadow over women’s lives and experiences today – both within medicine, and more widely shaping the attitude of society to women as workers, parents, individuals, and most vitally as humans. She highlights how women’s health has often been restricted to an understanding of reproductive health, with a woman’s fertility as a mark of her value, and she shows what a restricted and limited understanding that is. She speaks of how in the past women have been limited to the role of devoted wife and mother, with any variance from this pathologised and brutally treated with lobotomies, clitoridectomies and the ‘rest cure’. The book shows how progress has happened, with women speaking out against the treatment they have received and arguing to be heard.

Throughout this, Cleghorn doesn’t shy away from topics that are difficult to address, but engages with them using both compassion and honesty. She draws out the eugenics that are entwined with the early history of the birth control movement, the health risks and benefits associated with early methods of pain management during childbirth, and the huge doses of hormones delivered by early versions of the Pill, acknowledging the exploitation and abuse that sometimes was carried out in the name of progress.

Despite the challenging subject matter, and the ongoing difficulties within female healthcare, this book is far from hopeless. It offers a feminist critique of healthcare, acknowledging challenges such as the loss of Roe vs Wade, and the fact it takes on average seven years for endometriosis to be diagnosed. It also highlights what can be done, how women have worked together to care for their health, both historically and in modern society, and how women – both as patients and practitioners – have advocated to change society and make it listen to the voices of unwell women.

I was left with a sense of shock and horror at how medicine has failed women from its very birth as a discipline, but also with a huge sense of admiration for all those who have fought for women’s rights over time. Modern concerns over the menopause, menstruation and hormones have their roots far back in history, but they have been impacted by – and continue to be challenged by – those who have been willing to say that they are in pain, and those who are willing to listen and to believe them.